The work of 19th century mathematician Ada Lovelace can be accurately described in only one way… Ahead of its time.

Ada Lovelace was born in 1815 to a poet and a mathematician. The relationship between George Gordon Byron (Lord

Byron) and his wife Anne Isabella Noel Byron (Lady Byron aka Anabella) did not last long. Ada and her mother left

Lord Byron’s home within weeks of Ada’s birth, never to return. Lord Byron wasn’t known for being the family type,

and Annabella didn’t want her daughter to follow in her father’s footsteps. Thus, Ada was introduced to mathematics

and music from a young age (4 years old) and Lady Byron did all that she could to immerse her daughter in these

subjects so as to steer her clear of the romanticizing to which Lord Byron tended.

In the beginning when her mother was pushing so hard, Ada wasn’t particularly interested in learning mathematics…

(But who wants to do what their mom says…? :) Annabella thought that math and art were very separate, and that if

Ada was immersed in mathematics then her imagination would be under control. This, however, was not the case! Ada

had lots of ideas and her imagination was as active as could be.

As a young girl Ada wrote a book entitled Flyology, which was related to her idea for building a flying machine.

Presumably because horses were the main method of transportation, she sketched out her idea of the flying machine

as a horse with wings. She studied the structure of different birds to understand more about how winged creatures

could take flight, and she planned to power the machine by steam because that was the new technology of the time.

The idea unfortunately didn’t “take off”--especially because Lady Byron insisted that Ada turn her attention back

to her official studies.

Ada’s understanding of mathematics deepened as she aged and engaged herself more in the mathematical world, and she

began to rub shoulders with some of the greatest minds of the day… Among these were Mary Somerville, Augustus de

Morgan, and--most importantly--Charles Babbage. Her interactions with each of these people helped Ada to develop

ideas that she had, and to set her mind to helping their ideas take place.

Charles Babbage had interests in many different areas, but the work he did with Ada Lovelace was primarily on his

Analytical Engine. The two met years before, and Ada was very impressed by the Difference Engine that Babbage

invented, which was a kind of precursor to the Analytical Engine. Babbage’s Difference Engine was able to solve

polynomials and find roots, and because of this it could generate prime numbers. (Many were impressed by this

trick.) Augustus de Morgan’s wife, Sophia, noted that Ada seemed to have a much deeper appreciation for the machine

than most others, and that she seemed to understand Babbage’s explanations of how it worked--unlike most who went

to view it. She was only 17.

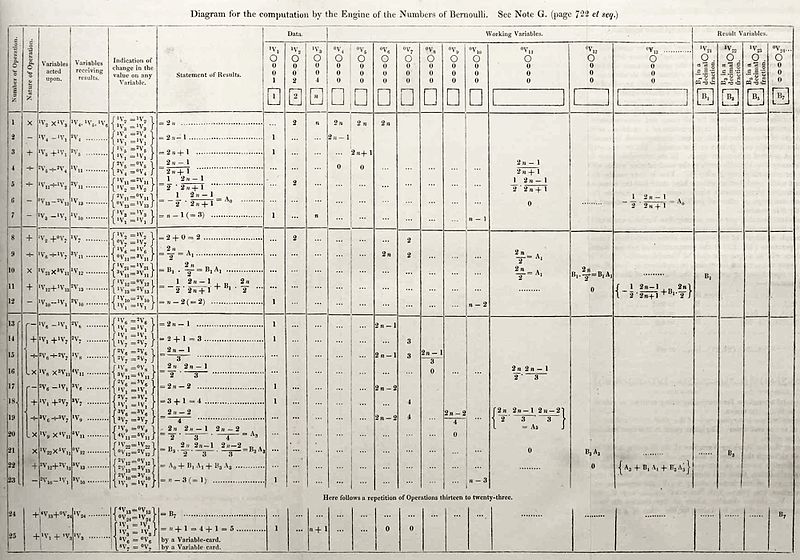

Luigi Menabrea, an italian mathematician, attended a lecture that Charles Babbage gave about his Analytical Engine.

He took several pages of notes explaining how the proposed machine was to work, and then Ada took over and wrote a

translation of the notes (called Notes G). The translation was three times longer than the original, and included

many ideas and improvements that Ada developed with the guidance of Babbage. This included, in part, the creation

of the first computer program.

Babbage’s Analytical Engine was never actually built, and the first computer didn’t exist until 100 years later.

But Ada had the imagination that her mother didn’t want her to have, and was able to envision what the Analytical

Engine had the potential of doing. She might have set even more stock in it than Babbage himself, believing that

the machine had the capability of manipulating symbols as well as numbers. This leads to the possibility of

manipulating pictures, music, words… This helped lead to the creation of the first computer.

If the thought of reading all of this daunts you and so you skipped to the end, feel free to watch this short video

that provides much of the same basic information.