In our day and age, not long after a child first learns to say ''Ma-ma'' and ''Da-da'' parents begin teaching their young to count. Numbers are something that most of us just accept as existing. But was there a time when they did not exist? If so, how did they come about? What did that in-between stage look like? What does it even mean to count? When we count, we are putting objects (or abstract concepts) into a one to one correspondence with a number word. (Flegg, 8)

What do we use numbers for? Everything. From buying clothes, to trading sheep for weapons, to football on Thanksgiving day, to tempurature, IQ tests, and speed limits. (See the following Ted Talk on numbers in history .) A much better question to ask would be: is there anything we DON't use numbers for? From medicine, to sports, to pan-handling, everyone uses numbers! Imagine a doctor trying to describe how much of a medication to take without numbers, or how to figure out which team won the Super-Bowl if we couldn't keep score, or if the amount of money someone just gave you is enough to buy lunch or not. A little later we will look at the development of more modern number systems, that are advanced enough to have position, negative numbers, and zero, but what was it like before that?

Even before people developed the idea of using number words, and being able to count, people still needed to somehow use numbers.

Imagine you are a shepherd with a flock of 53 sheep, in 4000 BC (Burton,2). The concept of the number ''fifty-three'' means nothing to you...but each sheep means a great deal. Because of you large number of sheep, you need some way to make it easier to tell if the same number of sheep come back home at night, as you let out in the morning. How do you ''count'' them?

You might use your fingers...but most of us do not have 53 of those, so you might need something that can accommodate more. You might decide to make notches on a bone, one for each of your sheep. You might decide to make add a single pebble to a growing pile for each sheep that goes out in the morning, and take one out of the pile for each one that comes home at night.

What you are doing here is creating a one-to-one correspondence between the sheep and something else, whether it be a body part, or a rock, a knotted rope, a stick, notch on a bone, or whatever else.

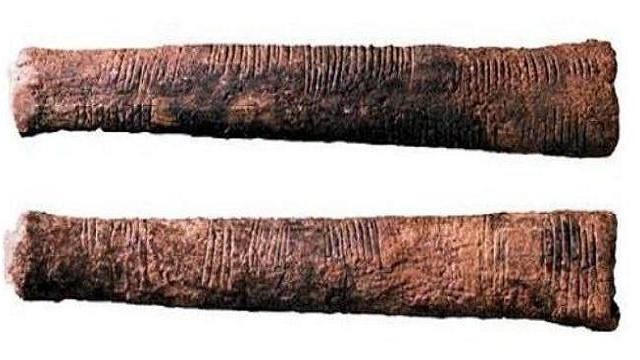

Bone artifacts have been found suggesting that people of the Old Stone Age had come up with some sort of tallying system as early as 30,000 BC. The most impressive example of this seems to be a the shinbone of a young wolf that was found in 1937 in Czechoslovakia. It is about 7 inches long and has 55 deep cuts in it, which are grouped in fives, similar to how we still use tally marks today. Maybe this wolf bone belonged to a hunter, and he was keeping a record of how many kills he had made, maybe it belonged to someone else who wanted to keep track of how many cycles of the moon had passed since he had found a mate. Whatever it was, this ancient person was definitely doing a primitive form of counting(Burton,2-3).

-

Interestingly, some civilizations became quite advanced with their body numbering methods. The Chinese, for example, developed a method of finger counting that allowed them to count up to 100,000 ...using only ONE HAND, and all the way to 1,000,000 when using two! Though primitive by today's standards, these early counting machines worked well and have had a lasting influence on us, from the counting me still do on our fingers, to the tally-marks we make when counting students in a class that prefer pink over blue, and how many blue over pink (Ifrah,).