One of the earliest forms of steganography was in 480 B.C. In the book Investigator's Guide to Steganography by Gregory Kipper, there is a story taken from a book known as The Histories, written by Greek historian Herodotus. Herodotus recorded that the Persian king, Xerxes, was planning to extend his empire "such that its boundaries will be God's own sky, so the sun will not look down upon any land beyond the boundaries of what is [their] own" (Kipper, 2003, p. 16). The Persians spent roughly 5 years secretly assembling one of the greatest armies in history.

However, the Persian military buildup had been witnessed by an exiled-Spartan king, Demaratus. Demaratus had been exiled from Greece and lived in the Persian city of Susa. Although he was exiled, he still felt a sense of loyalty to Greece and wanted to warn the Spartans of the Persian invasion plan. However, Demaratus feared that any message sent to warn the Spartans would be intercepted by the Persian guards. Herodotus wrote:

"As the danger of discovery was great, there was only one way in which he could contrive to get the message through: this was by scraping the wax off a pair of wooden folding tablets, writing on the wood underneath what Xerxes intended to do, and then covering the message over with wax again. In this way the tablets, being apparently blank, would cause no trouble with the guards along the road. When the message reached its destination, no one was able to guess the secret, until, as I understand, Cleomenes' daughter Gorgo, who was the wife of Leonides, divined and told the others that if they scraped the wax off, they would find something written on the wood underneath. This was done; the message was revealed and read, and afterwards passed on to the other Greeks."

The Greeks were unaware of any Persian attack, so they had not been gathering together an army. As a result of this warning, the Greeks began to arm themselves and were ready for the Persian attack.

Another example of Steganography in history includes the story of Histaiaeus, who wanted to encourage Aristagoras of Miletus to revolt against the Persian king. Histaiaeus shaved the head of his messenger, wrote the message on his scalp, and then waited for the hair to regrow. The messenger easily passed guard inspections because he apparently was carrying nothing suspicious. Upon arriving at his destination the messenger shaved his head and the message could be read. There are also accounts of shaving a rabbit's stomach, writing a message, and letting the hair regrow (Kipper, 2003).

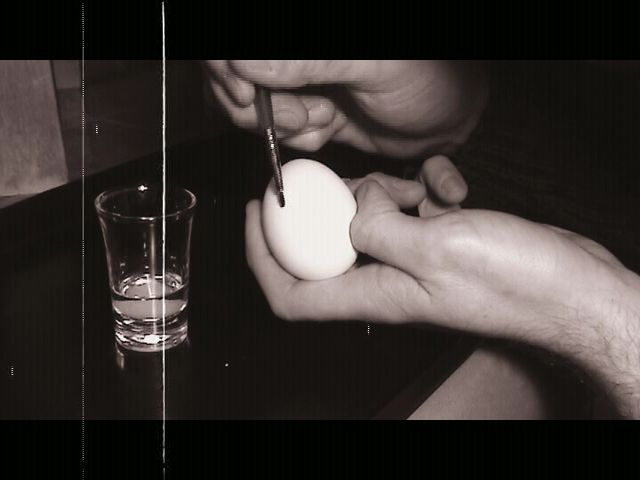

Other examples include that of the ancient Chinese. The Chinese would write messages on fine silk, which was then scrunched into a tiny ball and covered in wax. The messenger would then swallow the ball of wax. In the fifteenth century, the Italian scientist Giovanni Porta described how to conceal a message within a hard-boiled egg by making an ink from a mixture of one ounce of alum and a pint of vinegar. This ink was used to write on the shell of an egg. The solution penetrates the shell, and leaves a message on the surface of the hardened egg albumen, which can be read only when the shell is removed. (How to write a secret message on a hard boiled egg)